Delict: Flanagan v Minister of Safety and Security (497/2017) [2018] ZASCA 96

The appellant, Mr Earl Flanagan (“Flanagan”), was arrested on 10 October 2009 for driving under the influence of alcohol, reckless driving, and fleeing the scene of an accident. He was initially detained at Mount Road police station and subsequently transferred to Walmer police station, both in Gqeberha (then Port Elizabeth). Despite a recommendation for bail by Inspector Erasmus, Flanagan was not released due to a series of administrative failures. These failures resulted in his continued detention over the weekend.

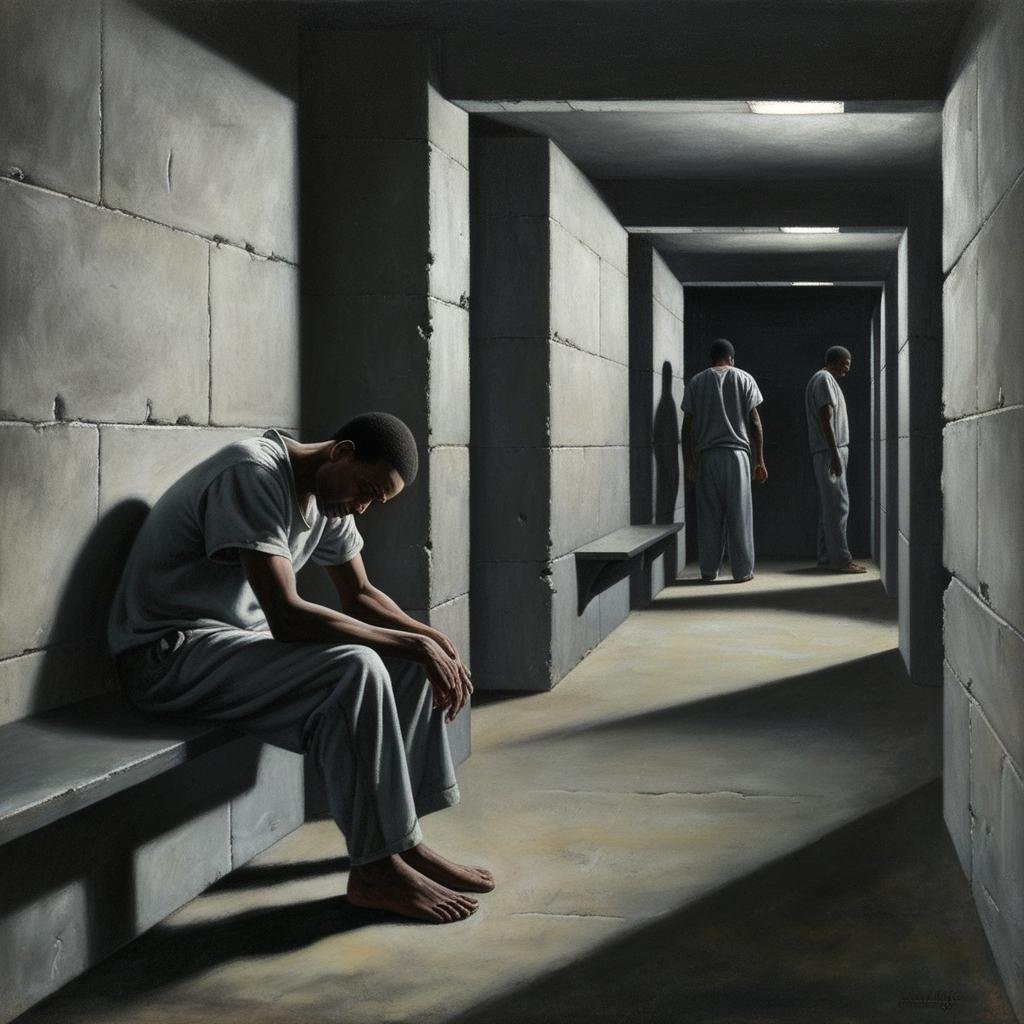

During his detention, Flanagan was sodomised by fellow detainees in the early hours of 12 October 2009. The police failed to separate him from detainees arrested for violent crimes, thereby breaching Standing Order 361. The appellant alleged that the police were negligent in their duty to ensure his safety while in custody and thus instituted action against the Minister of Safety and Security for damages.

Issues

- Whether the police breached their legal duty to protect the appellant while in custody.

- Whether the failure to release the appellant on bail and to separate him from violent detainees constituted negligence.

- Whether the police’s omissions caused the harm suffered by the appellant.

The Parties’ Arguments

The appellant contended that the police negligently failed to release him on bail despite his eligibility under section 59(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act (CPA).1 He further argued that the police had contravened Standing Order 361 by failing to separate him from detainees charged with violent crimes, thereby exposing him to an increased risk of harm. These omissions, he submitted, directly caused the assault and justified an award of damages for the ensuing physical and psychological trauma.

The Minister conceded the existence of a legal duty of care but denied negligence. He maintained that reasonable measures, such as hourly inspections of the prison cells, had been taken. The Minister further argued that the appellant had not established that his attackers were detainees charged with violent crimes or that the assault was reasonably foreseeable. It was also contended that no causal link existed between the police’s failure to grant bail and the subsequent assault.

Court’s Decision

The Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) upheld the appeal and found the Minister of Safety and Security liable for the police’s negligence. Its reasoning followed the established elements of delictual liability. First, conduct and wrongfulness were not in dispute. The respondent had conceded that the police owed a duty to protect Flanagan from harm. Secondly, however, the respondent denied that the police were negligent. The court applied the well-established test from Kruger v Coetzee,2 considering whether a reasonable person in the position of the police would have:

- Foreseen the reasonable possibility of harm occurring;

- Taken reasonable steps to guard against such harm; and

- Failed to take those steps.

Regarding the failure to grant bail, the court found that the appellant was clearly entitled to police bail under section 59(1) of the CPA because:

- The offences did not fall under Parts II or III of Schedule 2;

- The investigating officer had recommended bail; and

- The appellant posed no flight risk.

The failure to release him was attributed to a communication breakdown between police stations and to officers displaying a “supine and uncaring attitude”.

Then there was the issue of the failure to separate Flanagan from violent detainees. Clause 13(1)(g) of Standing Order (General) 361 requires that “whenever reasonably possible, persons in custody who are alleged to have committed violent crimes must be detained separately from other persons in custody”. The court found that this breach of Standing Order 361 created a real risk of harm and rendered such harm reasonably foreseeable.

On the respondent’s contention that the appellant failed to prove that his cellmates were violent detainees, the court relied on Marine & Trade Insurance Co Ltd v Van der Schyff.3 The court held that where a party fails to lead evidence on matters peculiarly within its knowledge, an inference may be drawn in favour of the opposing party. The court considered:

- The degree of risk, given that a person detained for drunk driving was placed among violent crime suspects;

- The severe gravity of the consequences given the nature of the harm; and

- The minimal burden of eliminating risk in that all that was required was proper classification or reconsideration of bail.

Regarding factual causation, citing Minister of Safety and Security v Van Duivenboden4 and Lee v Minister for Correctional Services,5 the court reiterated that a plaintiff need only establish that the wrongful conduct was probably a cause of the harm, not that it was the sole cause. A direct and probable chain of causation was found between:

- The failure to release Flanagan on bail;

- The failure to segregate him from violent detainees; and

- The sexual assault.

This finding was supported by entries in the occurrence book which noted that detainees charged with murder, robbery, and assault were present that weekend, with only the murder suspect being held separately.

For legal causation, the court applied the flexible approach from Delphisure Group Insurance Brokers Cape (Pty) Ltd v Dippenaar.6 The court considered reasonable foreseeability, directness, absence of a novus actus interveniens, and policy factors. The harm was sufficiently closely linked to the omissions to ground liability, and no policy considerations militated against the imposition of liability.

The appellant was awarded R200,000 in general damages for psychological trauma.

Author’s Opinion

The judgment affirms the principle that police bear a substantive duty to ensure the safety of detainees, including through procedural safeguards such as the assessment of eligibility of bail and the classification of detainees. However, the quantum of damages awarded appears inadequate given the severity of harm sustained.

Mr Meyer, a clinical psychologist, gave unchallenged evidence that Flanagan experienced severe psychological trauma as a result of the assault. Six years later, he remained on antidepressants and tranquilisers for chronic anxiety and insomnia, with only limited therapeutic benefit. The trauma had induced humiliation, fears of HIV, and a near-marital breakdown. Sexual dysfunction and emotional withdrawal further strained his relationship.

In the workplace, the assault precipitated flashbacks and absenteeism, followed by ridicule from colleagues and eventual dismissal. Flanagan attempted suicide, was hospitalised for five days in intensive care, and exhibited long-term personality changes including withdrawal, irritability, and aggression. He expressed self-loathing and emasculation, at times telling his wife to “find a real man”. He was diagnosed with PTSD, mood and anxiety disorders for at least eight months. Mr Meyer’s assessment was consistent with testimony from Flanagan and his wife, both of whom confirmed the pervasive impact of the assault on every aspect of his life. The trauma was enduring and, in many respects, irreparable.

The court referenced De Jongh v Du Pisanie,7 which cited Pitt v Economic Insurance Co Ltd,8 where Holmes R stated:

“[T]he court must take care to see that its award is fair to both sides – it must give just compensation to the plaintiff, but it must not pour out largesse from the horn of plenty at the defendant’s expense.”

Judicial conservatism in awarding general damages is well-established, reflecting a concern for fairness towards defendants. The award in this case is consistent with that trend. However, R200,000 (roughly R272,380 when adjusted for inflation at the time of writing) is, in my view, grossly inadequate given the aforementioned harm suffered.

There are, by contrast, instances where courts have adopted a more realistic stance. In T.M.A. v Minister of Police,9 the plaintiff claimed damages following his arrest and detention from 25 May 2015 until 26 July 2017. He alleged that South African Police Service (SAPS) officers assaulted him during arrest and that he contracted HIV in custody due to forced tattooing by inmates. He also claimed significant psychological trauma.

Although SAPS argued that the plaintiff’s post-court detention fell outside their control, the court, citing Mahlangu v Minister of Police,10 held SAPS liable for influencing the denial of bail by withholding exculpatory information. Relying on Woji v Minister of Police,11 the court found that the failure to disclose the plaintiff’s cooperation to prosecutors materially influenced his prolonged detention. The plaintiff was awarded R2 million in damages, consistent with other precedents such as Khedama v Minister of Police.12

While no monetary award can truly compensate victims of custodial abuse, the R2 million award in T.M.A. demonstrates judicial cognisance of the scale of trauma. By comparison, the R200,000 awarded to Flanagan appears paltry. This is exacerbated by the court’s award of costs for only two of the three counsel briefed, potentially reducing the appellant’s net compensation even further. Without specific knowledge of his fee arrangements, I cannot be certain whether Flanagan had to absorb the third counsel’s fees or they came to some understanding. It is possible. however, that a substantial portion of the damages awarded did not end up in his hands.

You can read the full Flanagan v Minister of Safety and Security judgement here.

You can also read the full T.M.A. v Minister of Police judgement here.

Written by Theo Tembo

- 51 of 1977. ↩︎

- 1966 (2) SA 428 (A). ↩︎

- 1972 (1) SA 26 (A). ↩︎

- 2002 (6) SA 431 (SCA). ↩︎

- 2013 (2) SA 144 (CC). ↩︎

- 2010 (5) SA 499 (SCA). ↩︎

- (220/2003) [2004] ZASCA 43 par [60]. ↩︎

- 1957 (3) SA 284 (D) at 287E–F. ↩︎

- (74452/2017) [2022] ZAGPPHC 813. ↩︎

- (CCT 88/20)[2021] ZACC 10. ↩︎

- (92/2012) [2014] ZASCA108 (20 August 2014). ↩︎

- 2022 JDR 0128 (KZD). ↩︎

Leave a comment