What is Dolus Eventualis? Revisiting the Pistorius Case.

The “Kill the Boer” ignominy looks set to remain a talking point for a little while yet. Having made its way to the ever-theatrical Oval Office of the White House, it seems to be the gift that keeps on giving. This week, Piers Morgan, the former Daily Mirror editor once turned professional phone hacker, hosted a few South African media figures to discuss the controversy. The conversation was brief but interesting in parts, and the full interview is available online.

What flew under the radar, however, was the opening part of the interview, in which Morgan spoke to Henke Pistorius, father of disgraced Olympian Oscar Pistorius. Henke commented on the “Kill the Boer” saga but also repeated his long-standing claim that Oscar was wrongly convicted of the murder of his girlfriend, Reeva Steenkamp. While Oscar, now out on parole, appears to have accepted the conviction, Henke insists the courts got it wrong and that prosecutor Gerrie Nel misled the court. So, why is Oscar’s father so convinced the conviction was flawed?

Pistorius Snr says it is “impossible” for his son to have been found guilty of murder. His argument is that Oscar fired only four shots, leaving 13 rounds in the chamber, supposedly indicating that he did not intend to kill. He also points out that all four shots were tightly grouped in an area the size of a brick and struck below waist height. To him, this suggests a lack of intent.

For those unfamiliar with the ins and outs of the Pistorius case, it marked a significant moment in South African criminal law. It gave the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) a chance to clarify an area that had previously been somewhat murky, namely the doctrine of dolus eventualis.

Intent is one of the key requirements for a murder conviction. In that sense, Henke is right: Oscar could not have been convicted unless the court found that he had the necessary intention. But it is important to understand that in law, “intention” does not always mean that a person aimed directly to bring about a specific result. Criminal intent can also include awareness that one’s conduct might lead to a prohibited consequence, and a decision to proceed regardless.

South African law recognises three main forms of dolus, or intention. Dolus directus, which is what most people understand as direct intention, where committing the crime was the accused’s goal. Dolus indirectus which applies when the consequence was not the aim, but the accused foresaw it as virtually certain and acted anyway. Then there is dolus eventualis, where the accused foresees a consequence as a possibility, reconciles himself with it, and proceeds regardless. To satisfy the requirement of intent, the prosecution can establish any one of these forms.

Returning to that fateful night in Oscar Pistorius’s apartment: only two people were present, and only one survived. There were no eyewitnesses to the incident, so Oscar’s version was the only one available to the court. Based on the evidence, there was no way to prove that killing Reeva Steenkamp was Oscar’s direct aim. Likewise, there was no evidence that he foresaw her death as a near-certain outcome, as would be required for dolus indirectus. What could be proven, however, was that Oscar suspected someone was in the toilet cubicle and fired four shots through the closed door. He testified that he believed it was an intruder, not Reeva, but that does not change the legal position.

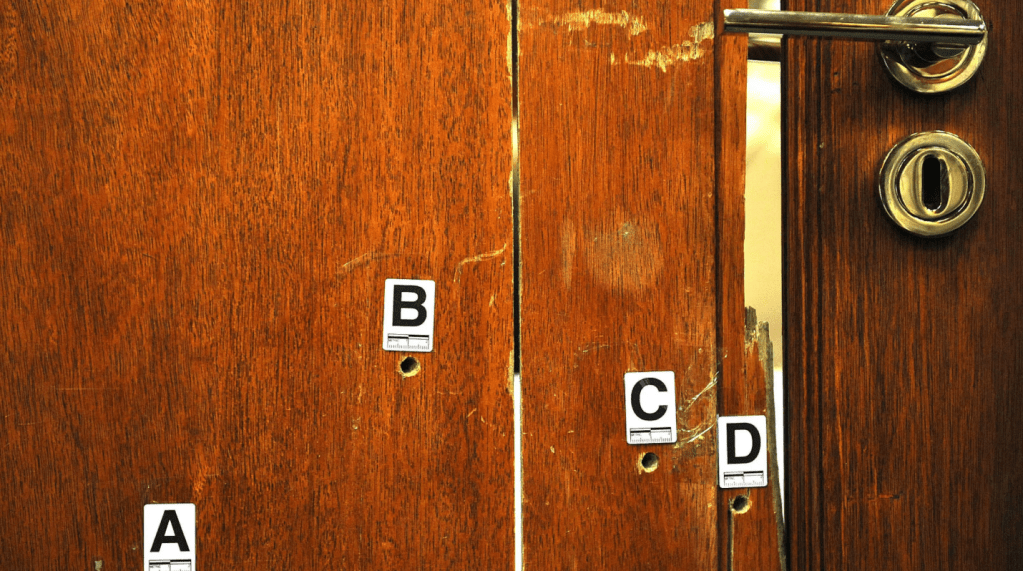

The real question is whether Oscar foresaw that firing four times into a confined space,1 at around waist height, might kill the person behind the door, accepted that possibility, and chose to shoot anyway. If he did, that satisfies the requirements for dolus eventualis. Legal intention in Oscar’s case was established on that basis. The court found that the State had proven, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Oscar knew shooting into a small toilet cubicle at about one metre (approximately three feet) off the ground might kill whoever was behind the door, and that he accepted this possibility and proceeded to shoot anyway.2 To find him guilty of murder, the law does not require that he knew it was Reeva behind the door. The identity of the victim is irrelevant. Had it been an intruder, the legal result would have been the same: he would have been convicted of murder for the death of the intruder.

Returning to Henke’s argument that Oscar had no intention to kill, based on the number and pattern of shots. That argument misses the legal standard. The court’s concern is not whether Oscar wanted to kill, but whether he foresaw that killing was a possible outcome and accepted that risk. That is the essence of dolus eventualis.

Before the Pistorius case, the application of dolus eventualis in South African courts had been inconsistent. In fact, in the court of first instance, the learned Judge Masipa had not applied it correctly either. It was only on appeal that the SCA settled the matter. Since then, the principle has seen more consistent and accurate application. For that reason, the Pistorius case stands as one of the most important in post-apartheid South African criminal law. Whether one agrees with the conviction or not, the legal reasoning behind it is sound, and it has left a lasting mark on how courts interpret “intention” in cases of murder.

I will end with the words of the SCA that convicted Oscar:

“In cases of murder, there are principally two forms of dolus which arise: dolus directus and dolus eventualis. These terms are nothing more than labels used by lawyers to connote a particular form of intention on the part of a person who commits a criminal act. In the case of murder, a person acts with dolus directus if he or she committed the offence with the object and purpose of killing the deceased. Dolus eventualis, on the other hand, although a relatively straightforward concept, is somewhat different. In contrast to dolus directus, in a case of murder where the object and purpose of the perpetrator is specifically to cause death, a person’s intention in the form of dolus eventualis arises if the perpetrator foresees the risk of death occurring, but nevertheless continues to act appreciating that death might well occur, therefore ‘gambling’ as it were with the life of the person against whom the act is directed. It therefore consists of two parts: (1) foresight of the possibility of death occurring, and (2) reconciliation with that foreseen possibility. This second element has been expressed in various ways. For example, it has been said that the person must act ‘reckless as to the consequences’ (a phrase that has caused some confusion as some have interpreted it to mean with gross negligence) or must have been ‘reconciled’ with the foreseeable outcome. Terminology aside, it is necessary to stress that the wrongdoer does not have to foresee death as a probable consequence of his or her actions. It is sufficient that the possibility of death is foreseen which, coupled with a disregard of that consequence, is sufficient to constitute the necessary criminal intent.”3

If you want to read more about dolus eventualis, you can check out an excellent article here.

You can also read the full Oscar Pistorius SCA judgement here.

Written by Theo Tembo.

- In the court’s words “The toilet was a small cubicle” (S v Pistorius (CC113/2013) [2014] ZAGPPHC 793). ↩︎

- Bear in mind, Oscar Pistorius was a trained user of firearms, and he fired the shots from about 2.2 meters (7 feet) away from the door. He did not fire any warning shots, even though his life was not in immediate danger at the time. ↩︎

- Director of Public Prosecutions, Gauteng v Pistorius 2016 (2) SA 317 (SCA) par [26]. ↩︎

Leave a comment